A few days ago, I heard a loud groan from downstairs. It sounded like a husband in pain. I went down to investigate. There he was, doing the crossword. The clue was “Less.” The answer was “Fewer.” Correct grammar had suffered another loss.

A few days ago, I heard a loud groan from downstairs. It sounded like a husband in pain. I went down to investigate. There he was, doing the crossword. The clue was “Less.” The answer was “Fewer.” Correct grammar had suffered another loss.

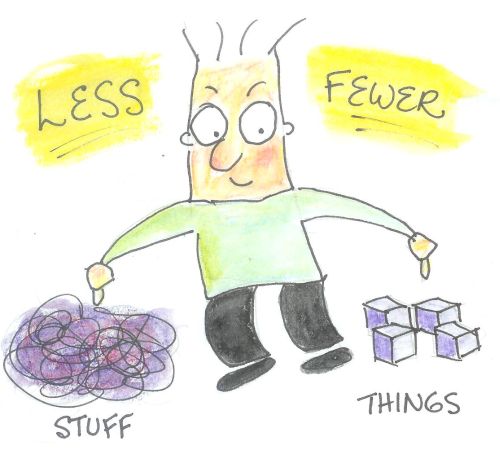

Less and fewer are not interchangeable. Less goes with a singular noun. Fewer is used with a plural. Less money – fewer coins. Less food – fewer biscuits. Less time – fewer hours. Less power – fewer kilowatts. Less trouble – fewer troubles. Less laughter – fewer laughs. In summary, you have less stuff and fewer things.

My first resource in any dispute over language is The Canadian Press Stylebook. Updated regularly, this guide to correct English was developed for journalists and has been adopted by business communicators, publishers and public relations practitioners across Canada. It has saved me hours of debate and struggle over my lifetime of writing. It confidently declares:

fewer Use with plurals: fewer bills

less Use with singulars: less sugar

Other sources are less confident. According to my second favourite resource, Fowler’s Modern English Usage, “Fewer is used with plural nouns (fewer books) and collective nouns (fewer people) and indicates number, whereas less is used with singular nouns and indicates amount (less money, less happiness). However, there is an extensive no man’s land between these two positions.” Then come several paragraphs explaining occasions when less might be OK with a plural noun.

The debate rages in many places, the Correct Grammarians pitted against the Evolving Languagers.

I suspect part of the problem people have honouring the distinction between less and fewer is that the opposite of both is more. We have more money and more coins, more food and more biscuits, more laughter and more laughs.

What’s not a laugh are those crazy collective nouns. Welcome to the English-speaking world. Take people, for example. It looks kind of singular – no S – but it’s about a crowd. When we’re talking about a crowd of individuals, the correct form is fewer people, not less people. And less crowds is never correct.

Why does correct grammar matter? Well, as I see it, when more people agree on the meaning and use of words, there are fewer misunderstandings and less confusion. I’ll say no more.

{ 0 comments }